103 years ago a woman was murdered. She was killed in a boomtown, a 14 hour drive east of here, here being Spokane, Washington, near the North Dakota border and where her mean man traveled to and fro – in many iterations, from Plentywood, Montana to Williston or Minot and back. He was afforded a multitude of roles and personalities, dimensions through space and time and lies and criminality that my Great Aunt Ethel was never allowed. Think of yourself as a 22 year old, which she was at the time – your brain is fast forming new wrinkles or adjusting some prior drama into maladaptive reactions. You are thrilled by violence, your entire age ruled by Mars and midnights getting drunk on illegal booze and wide open plains. You meet a bad man who looks real good, knows how to talk and has money and the power to move you from everything you ever loved. From a place where the only good crops were sunflowers and snakes. A mite like Hades, controlling the very tilt of your world and the seasons that rule your mood.

She met him presumably in Denver, where he was drifting through and she was looking to not become an old maid. Her parents, wanting to keep her safe from the wilds of eastern Colorado, sent her to live with her aunt in January 1920. By April of that year she had found and married Arthur. Their marriage license is so bereft of the essentials that most marriage certificates contained: race, age, occupations. No mention of whether they were related, no mention of witnesses. If it weren’t for this simple receipt of their union you would guess it never happened.

Ethel Gill was born the second youngest to Mollie and Lewis Gill in a small Kansas town, on a bright day in August, 1898. She was a leonine femme, with a slightly vamp look, who would grow into a big cat waiting for adventure. Her photos recall a time when eyes kept secrets. She looked tall, robust, built from her surroundings. She left home when the others in her family stayed close. Her big brother Roy stayed in Kansas, sending letters to his younger brother, my great-grandfather Chuck, in hand-painted envelopes. The letters came after Ethel’s death and retained a sense of good cheer. But Roy was the one to leave home to see Ethel put to rest. I’m sure he was provided no answers for what happened to her, but he maintained that Ethel killing herself was ludicrous.

He traveled by train from Cherryvale, Kansas to the hinterlands of Montana. A town settled and run by criminals – bootleggers and horse thieves – the exact type of man Arthur E McGahey, Ethel’s husband was. Between North Dakota and eastern Montana, Arthur executed a life on the fringes, in an effort to contain and whip power into a shape he could swallow and store for more fun, games, affairs and chaos.

Arthur’s Criminality

On the frontiers between child and adulthood, a 16 year old Arthur meted out justice by assaulting another young man with a horse shoeing hammer. The incident, not simply written off as a “boys will be boys” one, took Arthur to court to defend his violence. The urge to explode is not one contained to little lost boys of long ago, but still, a conscience should have grown in him by then – some semblance of common sense, a repression of his baser nature never took hold and this incidence with a deadly weapon was one of many in Arthur’s life. But instead of condemnation, his wrongdoings were skewed in favor of the type of profile that’d make your mama and papa proud.

Arthur’s crooked ways bent him between borders – between the slowly codified rules of a burgeoning West and its fringe characters, between states and women.

When Ethel was in cloth diapers in Kansas, Arthur paid an “insanity fee”, some sort of payment to authorities in Minot – a justification for such a fee I cannot find, but it was the second clue that maybe Arthur wasn’t all well. Two years later, Fargo local news reported on his resignation as Police Chief. Here I imagine he saw the inner machinations of a developing law enforcement and learned how to subvert it. Or maybe he misbehaved one too many times in his role as Police Chief and was forced to resign. His life of recklessness and cruelty, which I believe led to the murder of my great aunt, began long before her.

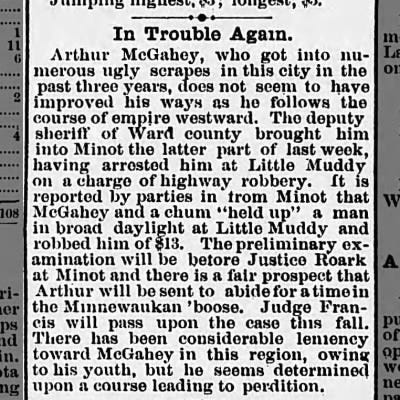

This splinter of a man, caught in the hand of nearly every man or woman who ever crossed him was renowned for bringing chaos from an early age. Highway robbery for the sum of $13 – aged 25. Six years later and none the wiser, Arthur is taken in for trading bullets with a man whose wife Arthur had been sleeping with. Then the Temperance movement in North Dakota created a fertile foundation for illegal alcohol distribution and Arthur built a black market for booze and beer out of a hotel basement. At the time, the name for these types of booze movers was blindpigger – an apt name for a man who destroyed evidence so that local law enforcement wouldn’t see a thing and have something to hang him on. Numerous regional newspapers covered his slip into legal contempt, a ruling that was later overturned by the state’s Supreme Court.

In between his thievery and rule-bending, Arthur, sometimes referred to as Art, or AE by local papers, found time for women. Not satisfied enough to simply sleep with them and move on, Art married, by my count roughly three women, with possible others strewn over his 67 years earthside. His first wife is Nellie Briscoe of Wisconsin – they are tied together in the 1910 census with a little one, Walter Lee. Later, he marries Elizabeth Sunderhauf, a woman who later fought Arthur for custody of their son, William. William was fetching bread the moment that my Aunt Ethel was supposedly aiming a .38 caliber revolver at her chest while dinner was being prepared.

Entangling Research & Family Histories

10 decades stacked on top of one another. Each decade, each year, each moment from her death on, no one has truly known what happened to Ethel. Or known where she was buried. One hundred years, give or take some, a grain fire that destroyed cemetery records, a lack of death certificates, a collection of dumbstruck, possibly colluding townsmen throws smoke in every direction. Everyday, across the world, including the United States, mothers, fathers, family and kin of all kinds mourn for loved ones lost, for murders unsolved. There is a collective ache, a vexed and complicated yearning to give definition and conclusions to their loved ones’ murders. I had learned of Ethel’s death through my mother and cousin, but more concretely through the stories they wrote and shared in genealogy circles. Somewhere in the stack of decades that I would eventually weed through, my grandmother shared her paternal family’s mystery. No one who knew Ethel thought she would kill herself. That familial itch was enough for me to scratch – for I am one motivated to solve, uncover, seek some sort of justice. I also research femicide, the killing of women because of their gender, and the more I researched Ethel’s death, the less it made sense.

All evidence for what happened to Ethel was mitigated through Arthur, a man who, as I’ve uncovered here, momentarily ran with the law, but more often than not broke it. He testified that she had “been despondent lately” and had “seemingly referred to suicide in a jesting manner.” He was also the only person in the home when Ethel died. His son was conveniently grabbing bread from the local bakery. After finding her prostrate on the floor, he ran to the local hotel to fetch someone, anyone, and appeared to be hysterical.

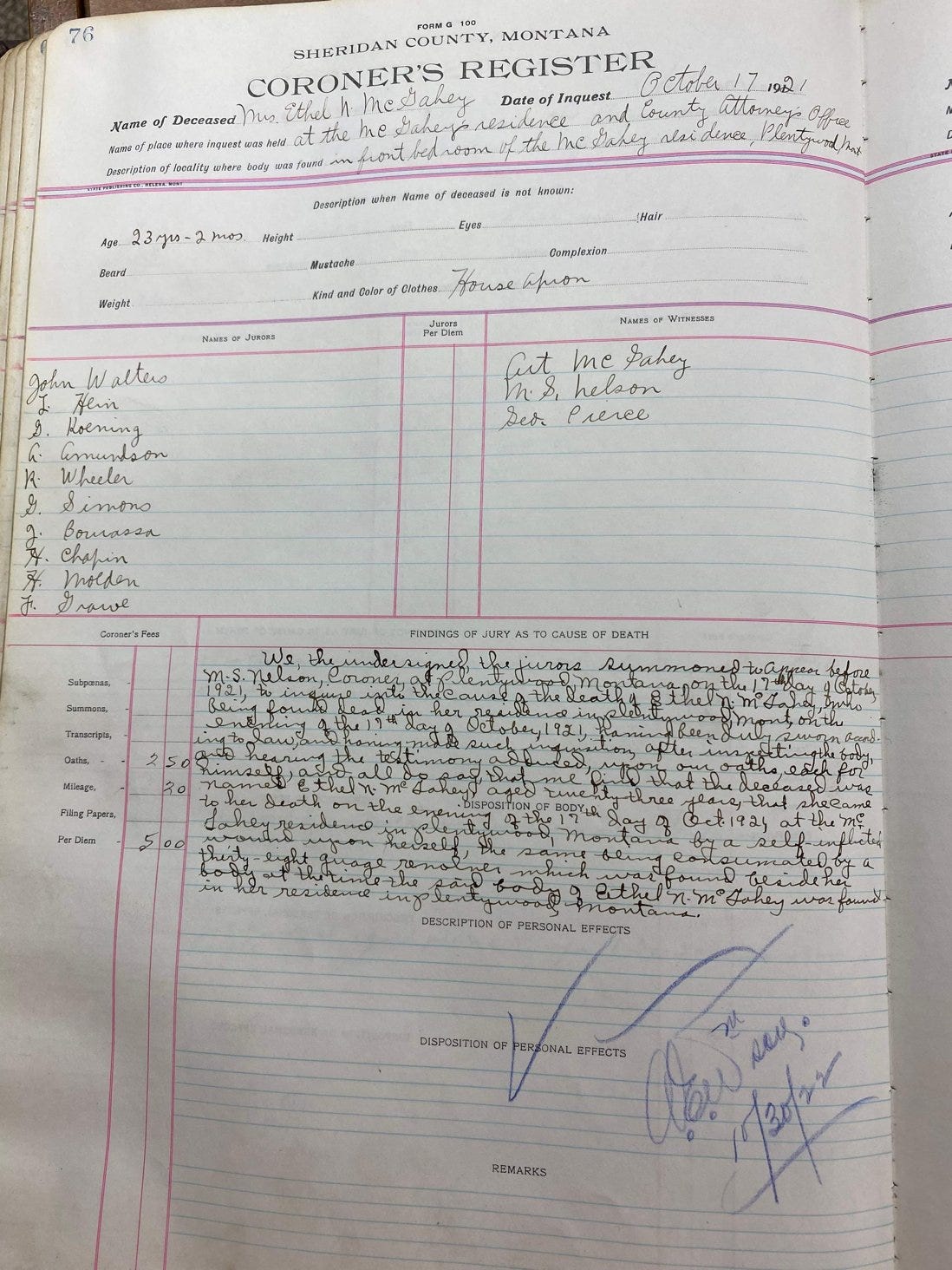

The day was spent joyriding. The four of them, Ethel, Arthur, William, and a fourth man, William Best, toured around the Montana countryside to pass the time. Coming home in time to make dinner, Ethel complained of feeling unwell and layed down. On the edge of the sun’s setting, vittles were stirred and steamed as Ethel supposedly moved from kitchen to bedroom, leaving the hearth-keeping to Arthur. Moments passed before a blast was allegedly heard and according to the sloppy inquest regarding her death, a .38 caliber revolver was found next to her body. The bullet had exited the left side of her body.

An inquest, composed of local men was hurriedly put together – the details scant, guilt assuaged and assigned back to the supposedly despondent and upset woman who no one knew. A man who was summarized as “very widely known” by Plentywood’s newspaper would go on to live 67 full years. A leg amputation, no more marriages and a return to North Dakota to finish his days with fishing and hunting before receiving a glowing summation of his life in an obituary. He would mysteriously come to live in his first wife’s home in North Dakota.

Arthur’s Spousal Abuse

But Arthur’s story does not end with Ethel’s death. His marriage to Elizabeth Sunderhauf was not neatly rid of, and its dissolution or lack thereof may have had implications for Ethel’s death. With the help of a records clerk in Montana I was able to read the 30 page divorce court proceedings between Arthur and Elizabeth from 1915. In 1915, less than one percent of marriages ended in divorce, a fact that gave me pause. What woman would risk divorce in an era of women’s indentured servitude endured through marriage. Why would anyone with limited economic mobility want to sever ties with a man who, according to divorce records, brought home $750 a month (roughly $22,000 in today’s dollars), who owned multiple buildings that housed local businesses such as the town’s saloon, blacksmith and butcher? Who owned their home and other commercial lots?

It only took a few paragraphs to identify why Elizabeth wanted to leave Arthur. From the record of divorce:

That since their said marriage, the defendant has treated plaintiff with extreme cruelty, in that the defendant, for more than two years last past, has inflicted upon the plaintiff grievous mental suffering that the defendant two years immediately before the commencement of this action, has repeatedly struck, beat and kicked plaintiff, thereby bruising, injuring and severely harming plaintiff, without cause or provocation, and has thereby caused her to suffer great mental and physical anguish and pain, and that defendant, during all of the said time has frequent occasions become grossly intoxicated, and while so intoxicated has used towards this plaintiff, vile and foul names and epithets, and has threatened to inflict and has inflicted upon the plaintiff grievous bodily harm, and that he has in the presence of plaintiff, mistreated and abused the infant child of the parties, and that he has otherwise grossly abused, injured and mistreated this plaintiff.

With two children under her care, and the odds against her, Elizabeth bravely confronted Arthur in divorce court and sought financial support for herself and for the care of her children. She appeals to the courts to freeze Arthur’s assets because, having known him a few years at this point, and having seen the cruel depths to which he would act, she knew Arthur would find a way to hide or sell everything he owned if it meant keeping it from her. She filed for divorce September 1, 1915. September 4 a motion is approved to freeze Arthur’s assets and award custody of their two children to Elizabeth. On September 13, Arthur was ordered to pay Elizabeth alimony and cover her court costs. The agreement, prior to trial, was temporary. On the 22nd, Arthur makes a case to sell two cows and a car, days later he is granted a reprieve and is allowed to do business as he sees fit.

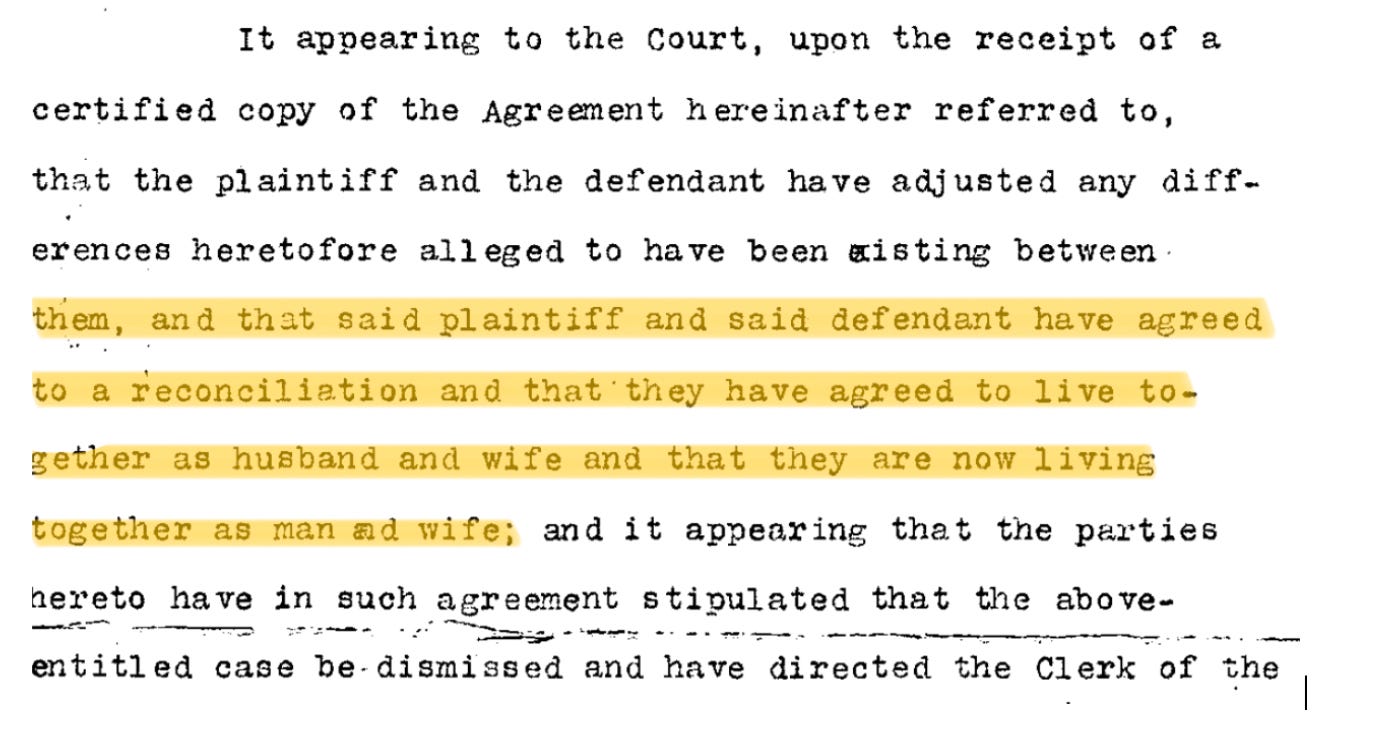

Then, on the 22nd day of October, something odd happens.

The divorce stopped.

What happened? Why would a woman who was brave enough to confront Arthur in court, brave enough to file for divorce in a time when divorce was exceedingly rare, back down? Did Arthur threaten and intimidate Elizabeth, or otherwise exercise coercive control to get Elizabeth to stop? The abuse Elizabeth endured, along with Arthur’s wealth (and having that wealth frozen) leads me to believe Arthur manipulated Elizabeth’s will. She had no other choice than to stop the proceedings.

Years later, after she had presumably extricated herself from Arthur’s grip, Elizabeth “kidnapped” their son, William. The sensational news story laid bare in newspapers from Washington to North Dakota, detailed how after years in court led Elizabeth to take custodial justice into her own hands led to an extradition request from North Dakota. Washington’s governor refused, claiming custody was still pending. In court documents I am still unable to locate, but that newspapers allude to, Elizabeth cites that William is dependent upon, but was neglected in Arthur’s care. Again, we must ask why anyone would go to great lengths to retrieve their child? Could Elizabeth have wanted to spare William from further abuse?

Taking into account Arthur’s individual criminal history, its intersections with Elizabeth and beyond, is it possible that Arthur was brazen enough to attempt and get away with murder? Are these facts alone enough to convict a man 100 years later? — not in a court of law, but in the heart of a far away descendent of the woman he murdered? What if anything, is there to do about this conclusion?

II.

The toughest part is not knowing who she was. This is a problem we see in media, both journalistic and artistic, where the woman whose life was snuffed out is frozen in a relief – like an ancient wall carving – only the perpetrator is animated and alive. Maybe it’s their rage and violence that feels life-full to us. In their murder, women are made once again passive and pliant, ghosts for us to project ourselves onto. I want nothing more than for Ethel to be more real to me.

In present day Spokane I sneak extra minutes from a work break to write funeral homes in Plentywood, Montana. I get a response that is jarring. Even with documented proof that someone died in their city – shrill newspaper clippings and a shoddy inquest supplied, they have no record of Ethel’s death or burial. Her spirit is simply lost without this knowledge.

At the beginning of December 2023, my mother recovered and started to transcribe audio recordings from my grandmother. In it, many gaps close in, new information surfaces or at the very least finer details are added to the image I’ve been largely painting on my own. Yes, Roy traveled to Montana, but we didn’t know he brought his shotgun. The train ride was free because Roy worked for the railroad. The shotgun was brought, I’ve assumed, to signify Roy’s distrust of Arthur and to protect him should the occasion warrant. Roy apparently noted later how old Arthur looked, thus confirming Arthur and Ethel’s significant age difference. A gap wide enough for Arthur to have had fully grown children Ethel’s age. Arthur could have been her father. So Roy went, but we don’t know if he was able to take Ethel back – to Kansas or Colorado. So the journey begins to try and find out where she is.

On a Sunday morning, after sleeping in and having the disadvantage of being two hours behind, my mother writes “he thought she was cheating” and I have a flash of justification. I acknowledge this lizard part of my brain shining through and then swat at it – none of that was justified. If Ethel cheated, if any woman or person cheats, that’s no justification for murder.

My grandmother’s words were transcribed to a group chat on a website created for social networking. Everyone of the people my mother mentioned in her transcription existed in worlds where social networking consisted of physically seeing and being seen in town. To hear tale of their lives – shaped and molded by hard labor and significant loss reminds me of how far away and yet how nearly connected I am to these people. How just because time passes doesn’t mean that they are forgotten. Their lives meant something – if not to the universe then to one another. They were all entangled into this thing called life – ribboned with electric energy sparked by consciousness and breath. I want to crawl back in time and have a physical form with them – see them be witnessed by neighbors and friends and know how Ethel’s murder fell like a shadow, with varying degrees of darkness, across their lives.