“In the end, there are just disembodied voices aimlessly floating in the air.” — Hisoyaka na Kessho by Yoko Ogawa.

I am one of those voices. And if you’re writing and commenting on the internet, you are too. There are many versions of us, deconstructing in a tonal prism of Greek choruses — humanoid chirps pinging as data across the walls of our dark, glistening, and private caves. Some voices are bright, and some are sharp, but all eke nourishment from the intangible — a cloud of data, hypertext, links, and chimes.

Reading Non‑Things: reclaiming humanity

In Byung-Chul Han’s book Non-Things, Han explores the yet-to-be world we find ourselves in: an earth where the edges of our human forms, along with our memories, dissolve. Where, “We no longer dwell on the earth and under the sky but on Google Earth and in the Cloud.” Where we have consciously moved into an era of information, or as Han calls it, the Infosphere and non-things. Non-things are digital, they are ephemeral, and they offer no grip for the human hand or body — they only require the flick of our fingers, a tool that in this transition has moved from making to choosing.

For Han, the antidote to non-things (data, information) is things. Things are the calm centers of our world. Things are the objects we sit and lie upon, open, play with, look at, etc. Things are physical objects that exist in the same place and time as us, and like us, they are impressed upon with gravity. We share a likeness with things in that the earth uses gravity to keep us close to her.

Arrestability: things, time, and death

Things, like us, are arrestable. Han centers arrestability in a realm defined to us by the likes of Arendt, Heidegger, and Walter Benjamin. Arrestability is a phenomenological quality, and it is something that can be held and dwelled upon. It offers resistance; it is a whole other, something that endures, degrades, and eventually falls away.

It is, unlike information, something imbued with the consciousness of death.

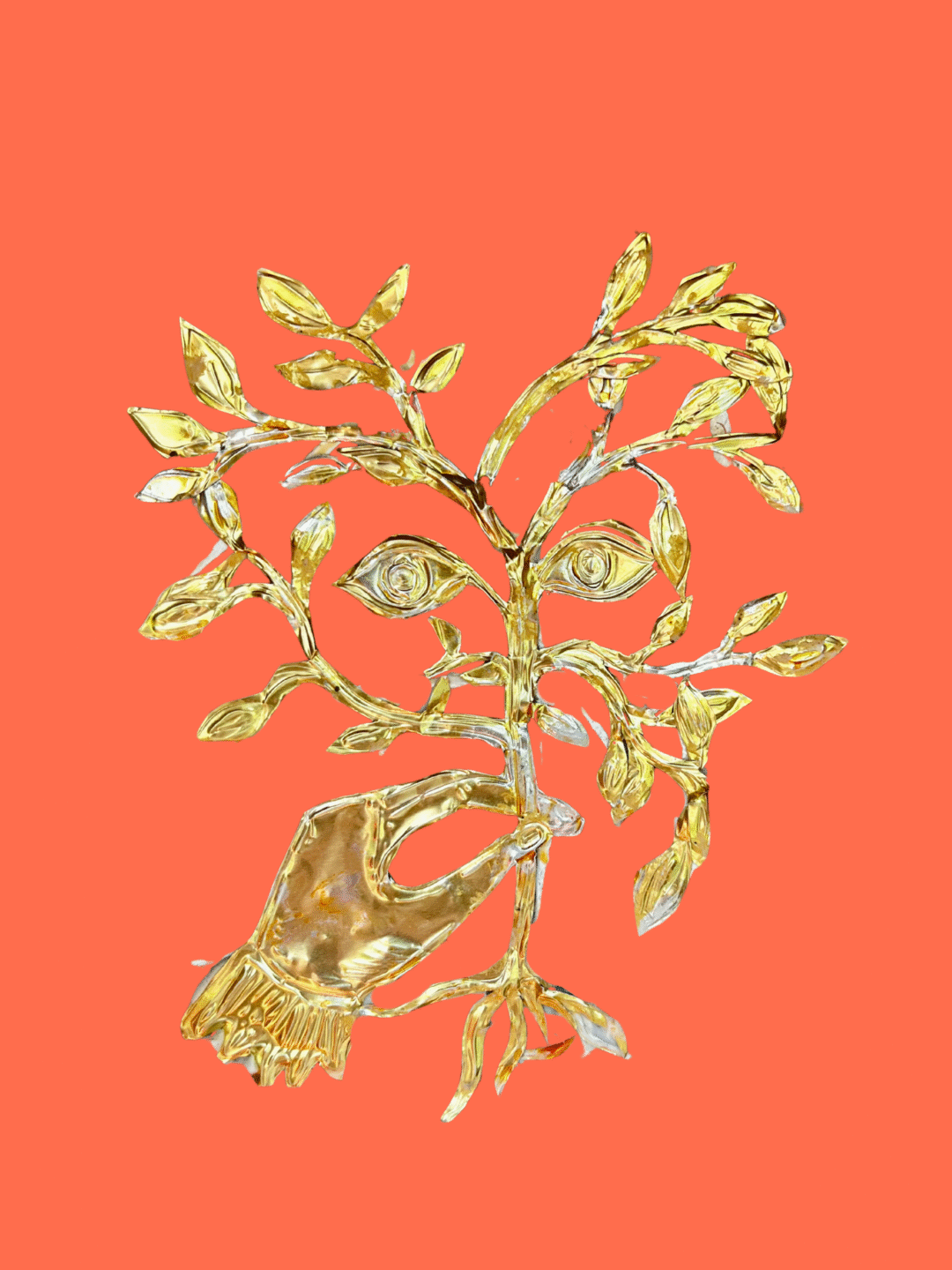

In his book, Han compels us to wonder what happens to the body and the spirit in the realm of the infosphere. What becomes of our bodies, our hands, and our loved ones if we drift away from the calm center of things — objects that offer us something to be in relation to? For Han, information dangerously de-reifies life; it takes away what animates and makes us sacred.

Han’s attention to that which makes us human and that which degrades us is on full display in Non-Things. Some of his explorations can feel retrograde, perhaps reactionary, but many others provided the kind of friction my spirit and intellect have needed for some time — so much so that I read Non-Things twice in the span of six months.

Han has me wondering: how do we prevail against the inevitability of information? How do we keep things holy, sacred, loving in the face of so much data and disembodiment?

Our Lost Faces

I’ve nearly stopped taking photographs with my phone. As a kid who grew up straddling the analog and digital divide, the novelty of having everything, including a small computer in my pocket, has worn off. The monthly process of moving digital photos from my phone to hard drive has gotten shorter and shorter over the years. Each folder, organized on a turquoise-shelled terabyte drive, has fewer and fewer images in its stock.

Analog memory vs. digital recall

Han’s thesis in Non-Things lays bare this shift in my attitude. These digital photographs are mere footnotes to a larger life. I scan them superficially for some hint of recognition of some long-ago moment. Conversely, my Fuji Film instant camera produces slim, desaturated photos of meaningful-to-me people and places. The transition to this physical format has prompted me to tape these special tokens to the pages of my notebook. During my travels from Eastern Washington State to Kansas a few summers ago, I took photos of roadside attractions, family, and friends. Now and then, I can flip through these taped pages and remember the exact circumstance in which these photos were taken. In many instances, I can remember the conversations, the smell of food cooking in the background, and the weather.

The physical reminder of my loved one’s presence is like a spiritual kindling of our shared time together. The physical photograph, with its unique texture and weight, binds me to them in a way that a digital photograph, which often languishes in a digital cell, rarely does. Each physical photograph is a unique and irreplaceable token of a moment in time, a testament to the value of the experience it captures.

For Han, “data is without light.” Digital capture is not of light, an unseeable, yet of the earth phenomenon. The photograph, Han and Roland Barthes attests,

“…is an ectoplasm, a magic emanation of past reality’, a mysterious alchemy of immortality: ‘the loved body is immortalized by the mediation of a precious metal, silver (monument and luxury); to which we might add the notion that this metal, like all the metal of Alchemy, is alive. Photography is the umbilical cord that connects the beholder to the loved body beyond its death.”

The physicality of photographs gives us an anchor to remember what is real. It is an antidote to the profane and forgettable non-presence of digital photographs. It is a thing, and unlike data, we can situate ourselves into a sensual reality by feeling the photograph, and thus feeling reality.

Thinking Requires Tension

Information is body-less. It is without consciousness, and it exists mainly as a mirage flagging on a faraway and ungraspable horizon. Accessing information online presents an opportunity for us to fully immerse ourselves in a world unlike our tactile one. Perhaps, like reading a book, it takes us into the loving arms of imagination. Han argues that the potential for “absorption” of data, or information, is minimal, and thus the disembodied state we enter when information-collecting does not mirror the bodily effects of, say, reading a book. Again, for Han, information is ephemeral; he states, “Perception that latches on to information does not have a lasting and slow gaze.”

For me, countering the chaotic splinters of information and data requires that lasting and slow gaze — a breath, an embrace back into my body — its weight and imperfections. It comes as sensation, the feeling of electricity of a room, through the radiohead that is my skin, or the gray and wiry hairs that catch my attention every time I pass a mirror. Out beyond the field of sensuality, you find your consciousness trying to locate itself, and it does so via relation — to words on a paper page, or to other creatures and creations.

I am not a Luddite (politically, yes, technologically, no). I have caught my eyes in the taxed and finger-smudged black mirror of my phone. They are hungry eyes, and sometimes they look into the digital canyons of YouTube for half hours at a time. But I’ve done much to curtail this sluggish instinct. I have made efforts to claw back my time from some of the most addictive platforms on the internet, and the reason I did so was to retain a sense of my own thinking — to bring myself into the productive type of tension that unfolds in the face of new and coherent ideas. In the walled gardens of Meta and X, the algorithm manipulates us into emphasizing temporary and ill-gotten social cachet over intellectual and spiritual development.

Algorithmic conformity and the body

Han illuminates, “He or she obeys algorithmic decisions, which lack transparency. Algorithms become black boxes. The world is lost in the deep layers of neuronal networks to which human beings have no access. “Living” in these online environments thus batters us into a type of neuroconformance, which becomes irresistible, addictive. In relation to an algorithm, we attempt to match its needs while fumbling in the dark. Results are chaotic, much like an unwell lover, and we remain unfulfilled, grasping. Our emotional maturity degrades, and we forget to match or mirror another person for connection, or lean into divergent thinking for the sake of creativity or problem-solving. This reality is devastating, not only for the future of ideas, but for the future of human connection and thriving.

How to Feel Alive — a Temporary Conclusion

Han’s work is challenging, but it is also a treatise formed in hope. It can be a dark thing reading about the dissolution of what makes us human, but Han ends Non-Things with an ode of sorts, on his love of a thing — an old jukebox. A person of faith, Han, creates to reify the world. In his insistence on the real, he gives me a faith that we can choose to embrace the real as well, that we can choose to build a world infused with deep and loving attentiveness.

This isn’t an essay about how I’m doing it better. This is my public insistence that I’m still failing, but trying to fail better. I am alarmed at the desaturation of our spirits, the beige-hued and meaningless hearts we splinter across the internet to strangers. Hanging the one and the zero in a uniform line, of conformance — coming from one scared kid self to another, a self that needs just to leave the house and join their friends on a hill, where collectively we overlook a 360-view of a better future, one with grassy knolls filled with picnics. One where I’m singing a song to you and you sing back out gently, and in harmony, and where you say to me with your eyes, I am real, hold my hand.

The header graphic for this essay was created by Derek Ortiz.