Taking time off, vacationing (for those of us who can), is so terrifying for the average American’s spirit. There are obvious hurdles that I subtly, parenthetically alluded to a moment ago, the primary of which is financial, and relatedly, a time poverty imposed on us by our rulers, benign or otherwise. But there’s also the terror of having enough time to break through the maintenance of everyday life to see who you are underneath all the “living”. Time away from your house, your job, your community, forces you to confront, in the words of Heinrich Karlsson, “being sentenced to freedom.”

It was Berlin, almost a month ago now, that something like a psychic splinter snagged in my thoughts. It was a generative trip — before that, I had been in London with an old friend, discussing identity, our shared experiences, and the commonalities between our Jewishness and our paternal descent from the Isles. Then, later, we discussed the identity of actors of color in British cinema, unfortunately cast into obscurity. My friend is widening and focusing the lens on actors like Lucius Blake, who seemingly toiled his way through odd jobs, all the way from Pittsburgh to being a consistent fixture in Britain’s early cinema.

Perhaps it was Lucius who woke the crisis in me. Hearing his story, I was confronted with the reality of art-making for its own sake, not for the response, accolades, or legacy. I also thought of Vivian Maier, the 20th-century street photographer whose works were discovered posthumously in a secret cache in Chicago. One of the central conceits of Finding Vivian Maier, the documentary about her, is the mystery of why she hadn’t shared her work. I bristled at this question then — sometimes an artist isn’t doing it for the notoriety, sometimes they’re simply making art for art’s sake.

But then the question arose: is Maier’s and Blake’s work simply a set of exercises, and if so, what differentiates these efforts from a hobby? Furthermore, does this differentiation matter to those who experience and enjoy these works?

From there, the questions got bigger: I come from a philosophical, psychological, and creative tradition that posits: Do the Work. No one Cares. And in that carefree-ness, worlds can manifest on pages and in the air. This realization was, at one point, very liberating for me. If no one paid any attention to what I was making, if no one was there to criticize me, I could do whatever I wanted. I could be free.

Of course, the flipside of this is a creative isolationism that, when absorbed and repeated, crushes any interlocking one can do with others – creative and communal growth is stymied. A belief in carelessness diminishes the gravity of one’s work. It’s also not true, as I have proven to myself many times over by continuing to care what other writers, artists, and musicians produce. These artists have profoundly changed my life, in small, microscopic, and sometimes unseen ways. Who am I to say their work isn’t important, and by extension, my work as well?

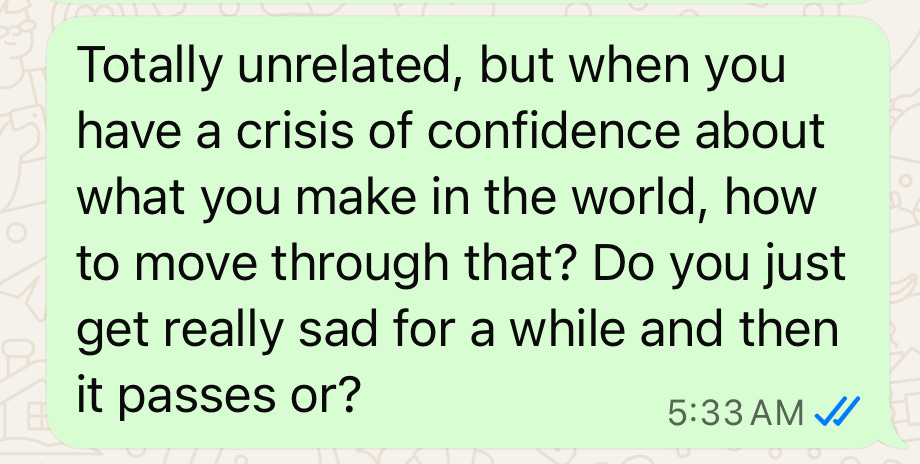

But back to Berlin. It was my second day in the city when a crisis of creative confidence arose. I reached out to my friend, whom I know would have some Thoughts about what was bubbling. There was something about the city, or a culmination of all of the above, that spiraled into existential questions about the point of human creation, and more specifically, my contribution to it.

My poor friend got this very early in the morning…

WHOOOOOSH. Creation’s hungry ghosts swooped in and feasted on a buffet of creative, existential questionings. I continued:

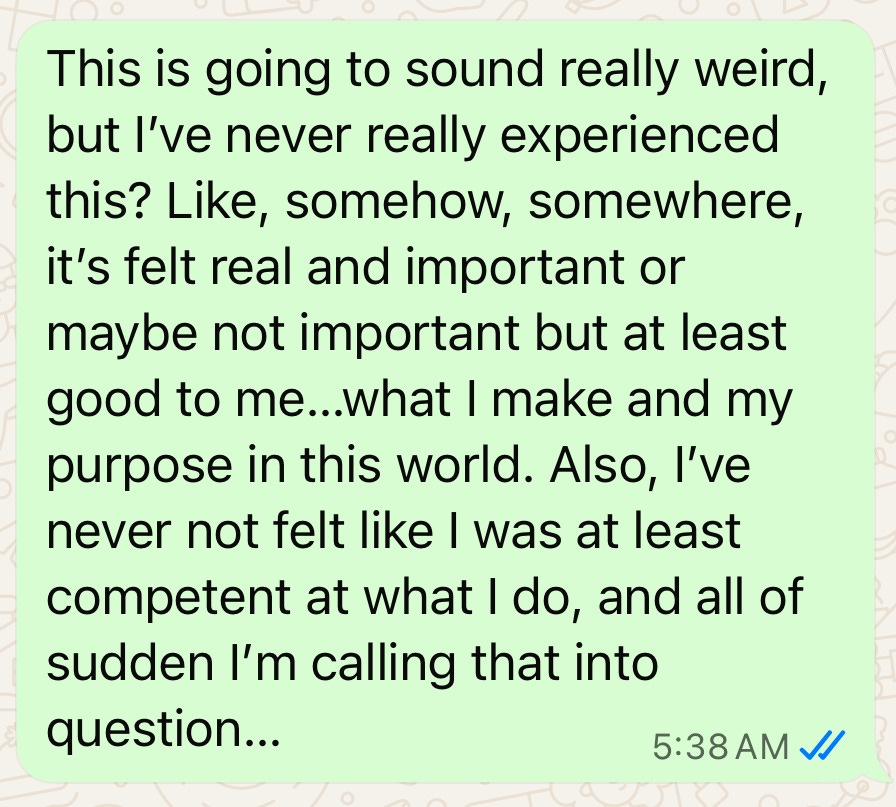

It says a lot that, in my 25+ years of making things, it took something, just what exactly I’m not sure, to tear away at my artistic beliefs and universe. That mysterious something forced a good, hard look in the mirror. There I found myself playacting at this whole endeavor. Like the court jester who sees Reality and jokes at it, but is just doing it as part of the ride — as part of some enjoyment of the process or delight in the thing as it becomes itself in front of us all.

I was doing all of this because I felt compelled to — and I shared with others because there is a small part of me that cannot help but do so. But as my friend discerned, deeper and deeper into my crisis, it became clear that One Who Creates must be willing to turn the thing over and determine if it’s simply a joy ride, or a craft — a practice that must be returned to, over and over again, because you can’t look away, and because in some way, you wholly believe in its worth and purpose. What does this do to your creativity when you treat yourself carefully and with more respect? What does it mean to take your work more seriously?

I don’t know; I’m still figuring it out.

And I still was then, through my friend’s thoughtful responses, and days later on the dance floor in some Umbrian hotel. The sun had just done its job on me — baking me as I officiated at my friends’ wedding, drawing on all my years of experience reading poetry out loud in front of people, using my voice as an instrument, to build tension and tone. To marry together two halves of a greater whole.

My skin was becoming a tawny red, and I felt dazed from the attention that I was trying to redirect — from the sun and the audience.

I took everything I had been thinking of on that trip and moved it through my body.

I took the question posed by my friend: Is it a hobby? And if so, that’s okay — but don’t get your feelings hurt when other people treat it as such.

Or,

Is it a lifelong, meaning-rich craft that you take seriously? If yes, begin now. Act as the charioteer and unite the wild forces within you to go, to move forward, with clarity of purpose and vision.

False humility onto the fire, my friend impelled. And this essay is the first log and kindling toward a funeral pyre for the self who denies what she needs — artistically and existentially. That is, to believe that what this is — this conflagration of words, heat, philosophy, beauty has meaning for me, and wherever you are, whoever you are being, that it has meaning for you too.